There’s a line in Miyazaki’s latest film, The Boy and the Heron (2023), that’s stuck with me for two years now. The film is about a boy, Mahito, who loses his mother in the western firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. He then moves to the countryside and discovers a tower that leads to another world. Mahito disappears into it, and his father, while looking for him, is told by an old woman that the tower “fell from the sky... just before the Meiji Revolution.” I thought that was an oddly specific detail for a Miyazaki movie, as they don’t usually denote historical periods, and I wondered why.

The Meiji Era, per Wikipedia, was a period from 1868 to 1912 when the Empire of Japan stimulated industrialization and moved from feudalism to capitalism. It was marked by The Land Tax Reform of 1873, which let non-royals own private property for the first time, the rapid installation of rail and other technologies, and the creation of a standing Japanese army modeled after the 19th-century French one. In the space of about five decades, Japan went from being an isolationist feudal country to an industrial capitalist powerhouse. Miyazaki, from what I’ve read, had mixed feelings about that.

In Lucy Jakub’s excellent essay on Miyazaki, she writes that he was born in 1941 to arms dealer parents. They made airplane parts for the Mitsubishi ABM Zero, the main combat model during World War II. During the war, ten thousand Mitsubishi ABM Zeros were made and 650 were used as kamikazes. After the war, Miyazaki majored in Japanese industrial theory at university, which would’ve certainly covered the Meiji Revolution. I get the sense it left a sour taste in his mouth. In an interview, he said that “No matter how much [people who design airplanes and machines] believe what they do is good, the winds of time eventually turn them into tools of industrial civilization. All of humanity’s dreams are cursed somehow.”

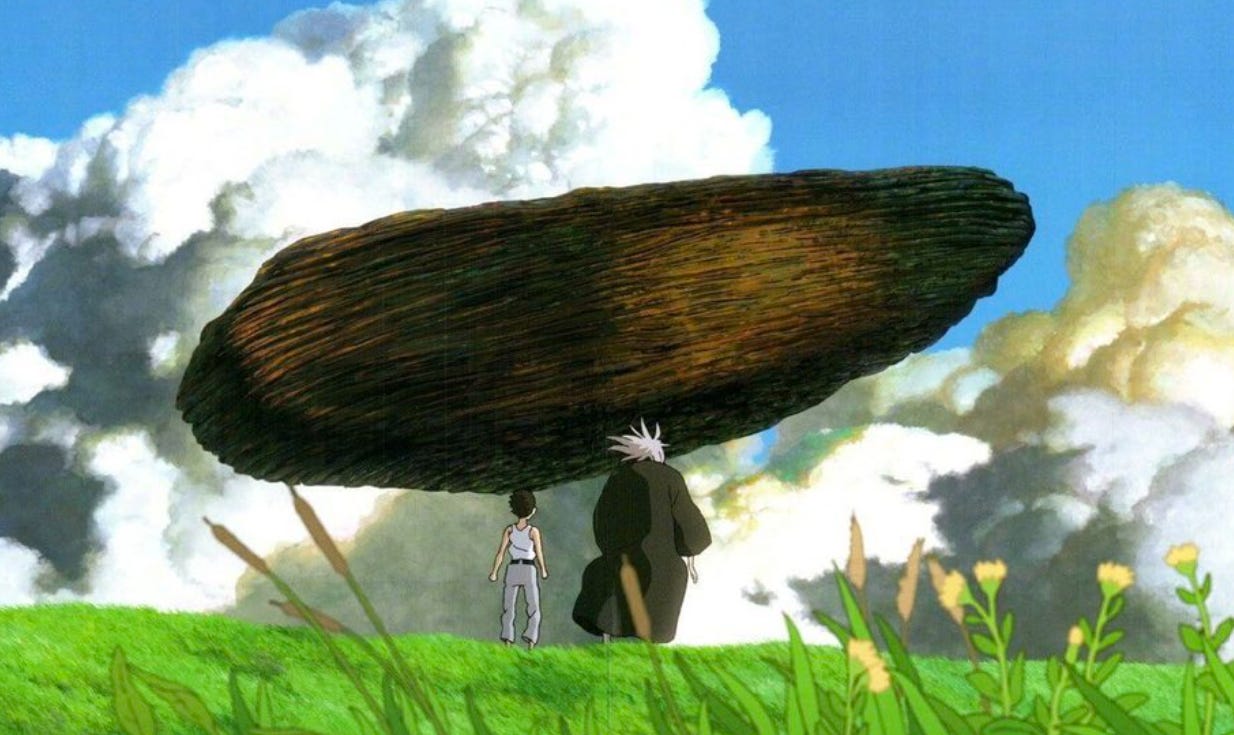

The Boy and the Heron features an alternate world where the Meiji Revolution never happened. In the film, Mahito’s aristocratic great-uncle creates that world using his tower’s alien power and disappears into it during Japanese industrialization. The tower’s reality isn’t industrial. It features vast oceans, islands with strange relics, and people who subsist by fishing in a communalist way of life. The tensions between environment-destroying industry and nature, which animate Miyazaki’s film Princess Mononoke, don’t exist in the tower’s world. There’s no “metabolic rift,” or what Marxist scholar Kohei Saito would describe as the gap between the pace of industrial production and how quickly the earth can replenish its resources. The tower’s environment remains unchanged, unlike Japan’s during the Meiji period.

Problems seep in nonetheless. The great-uncle, now a wizard, tells Mahito that “worlds are living things. Mold and bugs infest them,” and that the tower’s is decaying. The pelicans he imports can’t eat his oceans’ poisoned fish and consume its cute creatures instead. His parakeets develop fascism. The wizard exhorts Mahito to take over his world, telling him the real one will be “consumed by flames” soon and to create one of “bounty, peace, and beauty” within the tower, but Mahito refuses. He tells his uncle he’ll “go home and make friends,” escapes the tower, and takes his socialist ethics book How Do You Live? back to Tokyo with him at the end of the movie. Rather than go back to a pre-industrial time, Mahito chooses to explore an ideology that can reconcile industrialization and environmentalism in a way that capitalism never could.

I think The Boy and the Heron is a film about regret. In her essay on Miyazaki, Jakub writes that “Miyazaki always conjures a fantasy of refuge for his characters that’s not an escape from work, but a place where their work belongs to them alone: Ursula’s cabin in the woods, Howl’s castle stepping into the mist, Porco’s secret hideaway in a sheltered cove in the Adriatic.” In The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki presents that refuge as a site of failure. The wizard’s world is decaying, unsustainable, and his descendants don’t want it. His life’s work collapses and his dreams turn to dust. The only thing left for his heirs to do is to venture into the existing world, socialist textbooks in hand, and try to remake it in ways their ancestors couldn’t. Whether we can do that remains to be seen.

Tāmaki (Auckland) Events

The Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra is playing Handel’s “Water Music” at 7:30pm on Thursday, June 12 at The Holy Trinity Cathedral in Parnell. I’ve been really enjoying their work lately, having gone to other concerts for the past few weeks, and I think it’ll be good.

Recommended Reading

I liked this essay by Nicholas Russell on how the film studio A24 is developing a boutique version of Marvel’s marketing strategy. I wrote something similar a few years ago, localized to the films Everything Everywhere All At Once and Lady Bird, but Russell’s is much, much more comprehensive.

I liked this essay by Alicia Kennedy on having an editorial vision for your creative work.